Adam Elkus recently had an excellent analysis of the self-reinforcing aspect of the current Hollywood-Defense sector visions of the future over on War on the Rocks blog. In his article Elkus takes issue with the expectation that there is some obviously useful insight about the future of conflict to be derived from modern video games. I would agree with his assessment, particularly about military-themed video games. More broadly, science fiction is a field to which people have often looked for genuine foresight, and the debate about whether or not that is a useful expectation will no doubt continue to surge back and forth for the foreseeable future.

But while I do agree with his basic questioning of the expected foresight value of video game developers, I do have a couple of issues with parts of his critique.

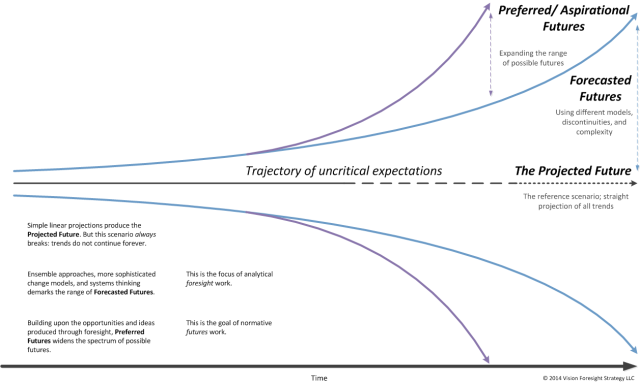

Elkus criticizes “defense futurists” of “presentism – the projection of the assumption of the present out to the future in a linear fashion.” This is a common – and typically valid – critique of a lot of forecasting. But the inverse critique, and one that is just as often leveled against foresight work, is that forecasters vastly overestimate the speed or degree of change that will occur. In essence, much of the world stayed the same and the forecasters were too gung-ho with their assumptions about disruptive change. Let’s call this “disruptism,” and one example with which Elkus might agree would be the demise of the State and the ascendance of the non-state actor in its place.

Elkus criticizes “defense futurists” of “presentism – the projection of the assumption of the present out to the future in a linear fashion.”

This stems from one of the core challenges in grappling with the possible futures of complex social systems: to usefully anticipate which elements of the present will remain unchanged in the future and which will undergo meaningful change. For a variety of reasons we are unable to truly predict (i.e. to know of a thing before it happens) the future states of these complex adaptive systems. As a result, the kind of big picture futures work of which we are here concerned has the fascinating but unenviable task of wading into that complexity and trying to anticipate what could change and why.

When we are grappling with this kind of complexity and uncertainty we are often at risk of both the presentism and disruptism critiques. Stick too close to current assumptions and we risk seeming uncritical. Stray too far afield from current assumptions and we risk being accused of producing science fiction. And we should remember that “current assumptions” are not just those beliefs held by top-level policy makers but also by subject matter experts who themselves play no small part in creating the narratives we all absorb about those current assumptions.

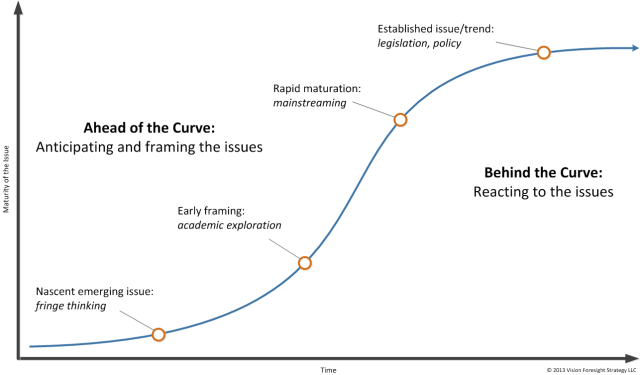

Elkus also references Kaplan’s 20-year old “Coming Anarchy” in his critique. While not arguing against any specific images he had in mind in his critique, I would offer that when it comes to emerging issues, just because people are drawing upon images of the future that may have been foretold long ago and failed to go mainstream in the time frame originally anticipated does not necessarily mean that they are foolish to draw upon them.

Some emerging issues that have obvious and huge disruptive potential are identified long before they mature. If bleeding edge/fringe/visionary types happen to get a meme foothold long before their issue moves up the survival s-curve, or if their issue happens to take a very long time to develop, then it may appear to subsequent audiences as if the issue is simply a perpetual “just-over-the-horizon” forecast that will never become reality. But many issues take far longer to develop and/or diffuse to the point of becoming critical issues, and over the course of their development are periodically dismissed as things that will never be important (consider 3D printing, ubiquitous computing, ebooks, and the rights of robots).

The thing to do is to unpack the forecasting that has been conducted. End users of foresight work, often laser-focused on taking their next set of actions, typically focus on the what of a forecast. What will happen? When will it happen? How much will it cost? But the mark of rigor and critical thinking in foresight work is revealed in how it was developed. Genius forecast? Crowdsourced consensus? WAG? And from this perspective, I am totally in alignment with the spirit of Elkus’ critique: being critical of the sources of our images of the future and the processes through which we attempt to develop foresight.

I do, however, find his later discussion about probability in futures scenarios to be the most problematic aspect of his critique. Elkus writes that real-world policy decisions cannot ignore probability or questions about what is likely. It certainly is true that clients often express interest in discerning the most likely scenario out of any set of forecasts. But it is here that I find perhaps the greatest distance between the kinds of quantitative forecasts produced around more specific phenomena (say, military coups) and the necessarily qualitative forecasts produced around much more open-ended questions regarding complex systems (e.g. whither the future of capitalism).

Every single person involved in a futures project, from the trained futurist to the just-hired junior executive thrown into a foresight workshop, has their own spectra of gut reactions and educated guesses about the “likelihood” of any particular forecast. But I have always found it difficult to apply any meaningful framework to generate probabilities for this kind of critical futures work dealing with broad and complex issues. There are certainly elements within these comprehensive forecasts that have useful notions of likelihood attached to them: demographics, cyclical changes, strong causal relationships between key concepts… But these are elements that get woven together with other less certain possibilities in order to contemplate the possible futures of complex things for which we cannot predict outcomes.

Elkus also mentions the need for “practicality” and I wonder if what he means is the same as what I and my colleagues would view as “logic.” It is especially important when grappling with difficult forecasting to ensure that logic is maintained at each step and across every scale. I find the most egregious mistakes in doing futures work comes from not applying real-world logic to how and why things change. What are common patterns (and causes) of technology diffusion? How does a particular industry typically react to catastrophic and high publicized mistakes? Exactly how do fringe ideas become social movements and eventually take their place as core assumptions in a community’s worldview?

In university we were taught that good futures work had to be based on theories of change and stability, and I’m sure that much of what that seems science fiction-y to serious audiences is partly the result of leaps taken without sound logic.

But even this trip down the path of pursuing more critical forecasting threatens to draw us away from the underlying purpose of futures work: to inform and motivate in order to both conceive of and pursue more desirable futures. Ultimately good foresight is about informing action towards creating a preferred future, not simply about generating ever-more-accurate predictions.

And still I hope against hope that The Division will see the light of day sometime this decade.

[…] up on my recent post On Games, Presentism, and Good Futures Work, below is a video from the Atlantic Council’s recent seminar on The Future of Unknown […]

LikeLike